THE EIGHTH ISSUE OF FIHRM-AP - Diasporic Memories in Taiwan: Life Journey of Tibetans in Exile

About the Author: Wen-Hsin Chang

A research assistant at the Exhibition Division of the National Museum of Taiwan History (NMTH), Wen-Hsin Chang specializes in difficult history, contemporary issues, and collaborations and co-creation between museums and international communities. Chang has curated exhibitions and published papers on topics including Taiwanese comfort women, sites of injustice, and new residents/migrant workers from Southeast Asia. She has also worked in projects including Correcting the Record, as well as In Their Own Voices- Victim-Centered Documentation and Memorialization of Forced Displacement, both organized by the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience (ICSC).

About NMTH

The National Museum of Taiwan History, herein referred to as "the NMTH," features Taiwan's history seen from a global perspective, with museology as its cornerstone. Shedding light on multiculturalism through the preservation of and access to Taiwanese cultural relics, historical dialogue, cross-border cooperation, and co-production of intellectual legacy with each participant seen equal, the NMTH tells the story of people and land from various perspectives that transcend ethnic groups. This vision makes NMTH a history museum of national level that promotes the maintenance of distinct cultural identities, while addressing contemporary issues.

Diasporic Memories in Taiwan: Life Journey of Tibetans in Exile

I. Diverse Ethnic Groups in Taiwan

Taiwan’s history is written by an array of ethnic groups. Over the decades, people living in Taiwan can trace their origin from all over the world. They relocate to start a new life due to various reasons, such as seeking survival, reclaiming new lands, carrying out mission work, as well as colonization and war. Over the past 30 years, there have been marriage immigrants and blue-collar migrant workers from Southeast Asia moving to Taiwan due to globalization, adding to the diversity of the immigrant community. Since 2013, the National Museum of Taiwan History (hereinafter referred to as the “NMTH”) has curated exhibitions including Movement of People- The Migration Stories in Taiwan and in 2017- The New Tai-ker: Southeast Asian Immigrants and Migrant Workers in Taiwan, which tell stories spanning generations of families and individuals moving across borders. With years of experience and co-creation with the community, the NMTH started an initiative in 2023 to curate exhibitions on non-citizen communities, bringing the public’s attention to diasporic groups hidden in the torrent of history.

II. Non-Citizens in Taiwan to the Present Day

From the 17th century to the middle and late Qing Dynasty, a large number of stateless individuals traveled between Taiwan and China, as they were not documented residents of the then Chinese Empire. The border of contemporary Taiwan was under strict control, followed by the lifting of Martial Law later. After Taiwan became a key player in the global industrial supply chains, cross-border exchanges of people and goods have become the new norm. Modern nations, judging from their trace of development, open up borders over time, but the costs and thresholds for entering a nation actually vary, due to an individual’s nationality, class, race, and gender. Those dwelling around borders are sometimes forced to move due to their nationality or personal reasons; there are also some seeking a better future. These displaced individuals and groups end up in Taiwan and become the so-called “non-citizens.” Some manage to settle down, others relocate again to other places, and still others need to hide their identity and live in disguise.

With the development of modern nations and the ongoing conflicts and oppression around the world today, individuals and groups who become “non-citizens” due to political or legal reasons have taken root in Taiwan, among whom Tibetans in exile is a prominent group. Their history and life in Taiwan can be seen as the microcosm of the complexities of global diaspora and transnational movement.

III. Diasporic Tibetans in Taiwan

According to statistics from the United Nations, the number of displaced people worldwide has exceeded 120 million, including those who do not possess nationality due to political or legal issues. There is currently an estimate of 160,000 Tibetans living in exile around the world, mostly in India and Nepal, and approximately over 1,000 having moved to Taiwan. In addition to those that first came with the Nationalist Government in the early days, the majority relocated under an anti-Communist banner adopted by the administration of Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo during the authoritarian period. After the lifting of Martial Law and the start of the Lee Teng-Hui administration, Taiwan received the visit of the spiritual leader His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. This led to a new chapter of the relations between Taiwan and the Tibetan government-in-exile; Taiwan, thus, became a stopover for Tibetan immigrants on their way to other countries. Some Tibetans came and obtained lawful residency or citizenship thanks to a sunset clause, while some are undocumented due to legal reasons. Tibetan Buddhism has become more prevalent in Taiwan since the 1980s, yet the voices of the Tibetans in exile on this island seem to have diminished over time.

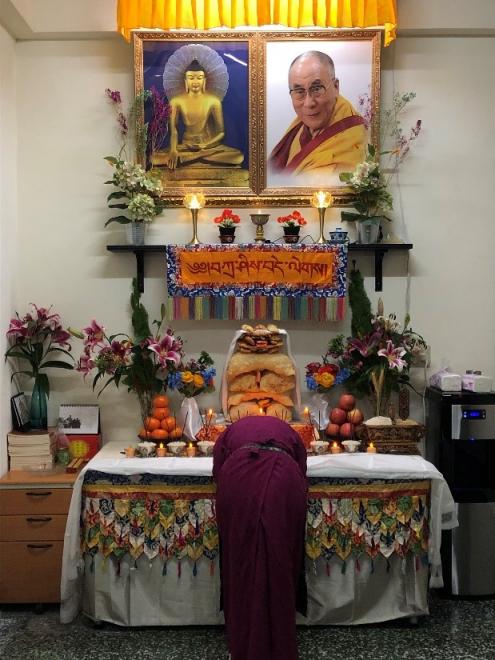

In Taiwan, second-generation diasporic Tibetans from India and Nepal have been educated mainly in English and Tibetan since childhood. With the Han people as the largest ethnic group in Taiwan, differences in language, dietary choices, and habits of life pose major challenges for these Tibetans to blend in. On another note, it is difficult for their children to receive Tibetan language education and to learn their culture. Many Tibetans in exile still have relatives back in their place of origin, but it has become increasingly difficult for members of their communities to make public appearances in Taiwan in recent years, due to the total oppression by the Chinese Communist Party in religion, language, writing, and culture. Despite the multiple factors that hinder these communities from fitting into mainstream society of Taiwan, there is still a strong bond among the community members. To preserve their identity and to pass on language and cultural legacy to the next generation, they try to bring together each member through events, such as classes for Buddhist teachings and Tibetan language.

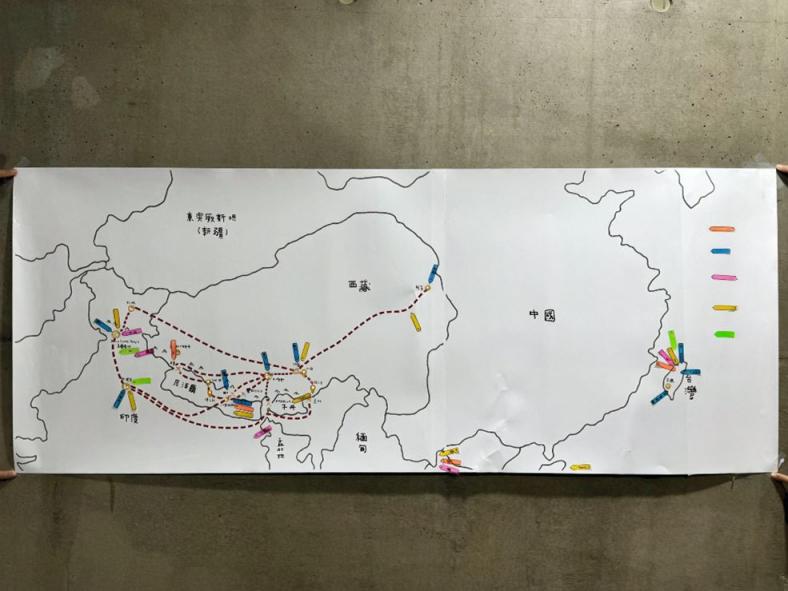

In one of the workshops for co-creation, the NMTH worked with diasporic Tibetans in Taiwan to map out their routes of moving to other countries.

IV. Curation & The Do-No-Harm Principle

The NMTH curatorial team, with the help from the Tibet Religious Foundation of the Dalai Lama, the Office of Tibetan Government-in-Exile in Taiwan, has built a trusting partnership with the Tibetan communities over time. Through the project- In Their Own Voices- Victim-Centered Documentation and Memorialization of Forced Displacement, led by ICSC, the Do-No-Harm Principle is adopted, that is, to avoid re-traumatizing the diasporic communities during curation. Participants will be able to join and leave the program at will and retrieve the provided information at any time. The NMTH must also obtain the consent of the individuals concerned before disclosing any information and ensure that the one suggesting personal identity is concealed, so that such data and statistics can be utilized within a reasonable scope. These criteria are followed to ensure participants’ privacy security at every part of the project.

For participants to disclose their personal experience in a safe space, the NMTH works with Tibetan musicians who have also relocated to Taiwan. In this way, participants can be engaged without pressure through mellow events with music and food. With sensitive information concealed, these people are encouraged to be part of co-creation by sharing their stories of moving across nations. Some followed the 14th Dalai Lama’s defection to Dharamshala in India all the way from their place of origin in China, while some are the descendants born in India or Nepal and they later obtained identity certificates through alternative approaches to enter Taiwan before they are eventually granted legal resident status. Everyone made it to Taiwan in different ways, but one thing they have in common is the facing the strict control enforced by the Taiwan government over the entry of exiled Tibetans, not to mention the things they have been through to take to the street when speaking for themselves to seek shelter.

On the surface, what these diasporic Tibetans in Taiwan have been through seems far from the experience shared among most Taiwanese, but in retrospect, it is not hard to see similarities and commonalities in the history of oppression, which is often closely related to the past and memory of this island.