THE EIGHTH ISSUE OF FIHRM-AP - The Cambodian Landmine Museum: One Mine, One Life

About the author: Bill Morse

Bill Morse and his wife Jill lived in Palm Springs, California for over 20 years. In 2003, they learned about Aki Ra's mission to clear landmines in Cambodia. Inspired, they founded the Landmine Relief Fund, a US 501c3 charity, to support him. Bill frequently traveled to Cambodia to help Aki Ra, who had adopted over two dozen children. In 2007, they helped establish Cambodian Self Help Demining (CSHD) after Aki Ra was ordered to stop his demining efforts. CSHD was certified in 2008, and in 2009, Bill and Jill moved to Cambodia to continue their work. Jill advises the Landmine Relief Fund and its programs.

About the Cambodia Landmine Museum and Aki Ra

Aki Ra, born in 1970, is a celebrated figure dedicated to making Cambodia safe from landmines. Taken by the Khmer Rouge at age 5, he fought in various armies for nearly 35 years. In the early 1990s, he worked with the UN to clear landmines around Angkor Wat. He founded the Cambodian Landmine Museum and Relief Center in 2007 and the Cambodian Self Help Demining organization in 2008. After retiring from active demining in 2023, he focused on running the museum and raising awareness about landmines.

The Cambodian Landmine Museum: One Mine, One Life

I. Bombs Over Cambodia: Vietnam War and the Rise of Khmer Rouge[1]

The United States began bombing Cambodia in the mid-1960s to prevent the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), which had built a roadway through Laos and Cambodia to move soldiers and supplies from North Vietnam into South Vietnam. Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger escalated the bombing after 1970. In total, over 65,000 bombing missions dropped over 3 million tons of bombs on Cambodia from 1965 to 1973. This bombing destabilized the country, leading to the overthrow of the government in 1970 and ultimately to the capture of Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975, by the Khmer Rouge, a radical Maoist organization determined to return Cambodia to its agricultural past and eliminate the middle and upper class.

The Khmer Rouge killed nearly 2,000,000 people to purify the country. They were overthrown on January 7, 1979, by the Vietnamese Army, supported by expatriate Cambodians who had fled to Vietnam. Fighting continued for nearly 20 more years. A standard weapon of choice is the landmine. Millions were laid, and none of their locations were recorded.

The fighting ended in the late 1990s with the death of Pol Pot, the leader of the Khmer Rouge, and the surrender of the last of its forces to the Cambodian Army. The millions of landmines planted during the war continue to threaten the safety and lives of the Cambodian people.

II. The Origin of Cambodian Landmine Museum

The Cambodian Landmine Museum was founded in the early 1990s to tell visitors the horror of landmines and unexploded ordnance through the story of one small boy, suppressed into service as a child soldier. His name was Aki Ra. Stolen from his family by the genocidal Khmer Rouge at the age of 5, he became a child soldier when he was 10 years old. He fought with the Khmer Rouge, radical communist movement that ruled Cambodia from 1975 to 1979, until he was captured and forced to join the Vietnamese Army. When the Vietnamese left in 1989, he became a soldier in the Cambodian Army. In the early 1990s, he began clearing landmines. He discovered he was adept at removing these dangerous weapons, many of which he had put into the ground, so he started looking for anything he could find. Often contacted by local villagers and police, his objective became to ‘make my country safe for my people.’

Aki Ra’s original museum was built along the Siem Reap River in the city of the same name. It consisted of wooden buildings cobbled together and surrounded by a fence. Aki Ra cleared landmines wherever he found them. He defused them by hand or blew them up, using techniques he developed. Unlicensed by the government, he was sometimes in conflict with local authorities. He was not the only person trying to demine the countryside; some others were blowing themselves up.

During his travels to make his country safe, he found several orphaned and abandoned children, landmine victims. He brought them home, fed and clothed them, and ensured they went to school.

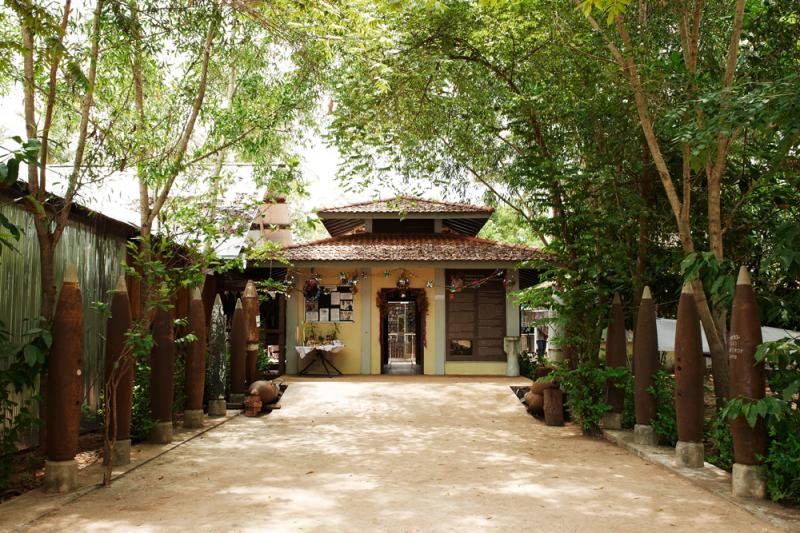

In 2007, his original museum was closed. There were questions about land ownership and none of the ‘decommissioned’ ordnance had been inspected and certified safe by the government. With the help of a Canadian organization, the museum moved to its present location in Banteay Srey, inside Angkor Wat National Park. It became the home to over a dozen orphaned and abandoned children, many landmine victims, until 2018 when the government began closing unlicensed residential centers. All the children who lived at the museum either moved home or were relocated to government approved facilities.

III. The Institutionalized Process of the museum and its sister NGO

The Support from Landmine Relief Fund in 2003

Aki Ra had to start an NGO that the government would approve to receive a license. In 2003, an ex-commissioned officer in the US Army, Bill Morse, heard of an ex-Khmer Rouge soldier, Aki Ra, whose quixotic mission was clearing landmines by hand. He and his wife Jill traveled to Siem Reap, Cambodia, to find Aki Ra and learn more about his work. After meeting him, he returned to the US and started the Landmine Relief Fund, a 501c3 charity, headquartered in Palm Springs, California to help support Aki Ra’s work.

Bill Morse's wife Jill

The Establishment of the Museum’s Sister NGO, Cambodian Self Help Demining (CSHD) in 2008

With the help from the Landmine Relief Fund, Aki Ra applied for a license to start a demining team and work ‘within the system.’ The Landmine Relief Fund raised the money to send him for formal training in the UK to certify his abilities. The training reinforced his expertise, and the certification convinced the government that he was indeed a qualified expert in demining. A license was issued, and Cambodian Self-Help Demining (CSHD) was founded in 2008. Aki Ra was the director of the NGO from 2009-2023, when he retired to concentrate on managing the Landmine Museum.

IV. Dedication to Clearance and Education of Landmine

Aside from landmines, the country is rife with unexploded ordnance, bombs, mortar rounds, artillery rounds, and other ‘explosive remnants of war’ that regularly kill and maim children and adults. In the 1990s, there were more than 1,000 casualties a year. In 2023, there were less than 40. Clearance and education have reduced the number of casualties tremendously.

Phase I: the Removal of the Mine Field

Cambodian Self-Help Demining (CSHD) today fields one demining team, two Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) teams, and an Explosive Ordnance Risk Education team that provides classes in villages and schools teaching locals how to recognize, mark, and report suspicious materials. To date, the demining unit has cleared over 250 minefields covering nearly 9,000,000 square meters of land and returned tens of thousands of people to land that was, in every sense of the word, killing them.

CSHD began clearing minefields in 2008. Most of the fields they cleared were along the Thailand/Cambodia border, where American bombs had been dropped from 1965-1973, where the Khmer Rouge were dug in, and infrastructure was difficult or impossible to create until the fighting stopped in the late 1990s. In a tiny village, Dong Tong, the village chief, asked CSHD to help them build a small wooden school. The two women in the town who could read and write would become the teachers. It took the team about a month to build a crude wood schoolhouse with a dirt floor. The Landmine Relief Fund purchased school supplies and paid the teacher a small stipend. Within a year, the new Minister of Education allowed this school and other wooden schools to become part of the Cambodian school system. This brought in certified government teachers and put the students into “the system.”

Phase II: Building Rural Schools (The Establishment of the Museum’s Sister NGO, Rural School Support Organization in 2019)

The Landmine Relief Fund continued assisting CSHD in building rural schools. By 2018, it became clear that the school building program needed to move outside CSHD and become its own NGO. Rural School Support Organization (RSSO) became an NGO in 2019. As of April 2024, RSSO has built 32 schools in 7 provinces, helping nearly 4,000 primary-aged students receive an education. RSSO works with the villages to identify a hectare of land deeded for a school. When the town gets permission to have a school, the Landmine Relief Fund raises the necessary funds to put up the building and equip it with desks, blackboards, and textbooks. They also provide school supplies for all the students. It costs $30,000 to build a fully furnished 4-room schoolhouse.

In 2019, RSSO established The Together Project, a “teaching farm” that teaches people to grow organic crops. They teach hydroponic and greenhouse farming, as well as mushroom-house farming. All classes are free. Funding is provided by the Landmine Relief Fund. The school was founded and is run by a graduate of The Royal University of Agriculture, who grew up at the Landmine Museum.

V. Current Status of the Cambodian Landmine Museum

The museum consists of four galleries around a pond. In the middle of the pond is a glass-enclosed gazebo that houses several thousand decommissioned landmines from Russia, China, America, East Germany, Vietnam, Cambodia, and the old Soviet Union republics. Aki Ra and his demining teams removed all of them.

Collections of Mines in the museum

Collections of Mines in the museum

One of the difficulties the Landmine Museum always had was the inability to tell its story in enough languages to meet the needs of its ever-increasing tourist visitors. It first introduced written guides in 7 languages. Now, there are QR codes in each gallery explaining the exhibits in English, French, Chinese, German, Italian, Spanish, and Russian. Tour guides give tours in Cambodian and English, concentrating on the history of the conflict in Cambodia, the use of landmines and other explosive remnants of war, and their continuing threat to the people of the country.

Tours given to Cambodian citizens are significantly different from those given to foreign visitors. Foreigners, Barangs (foreigners), are taught the history of landmines in Cambodia and how they are being removed. Cambodians are given a ‘mine risk education’ class, telling them what to look out for when they visit the countryside, how to identify threats, mark them, and who to call.

VI. The Museum’s Ongoing Mission and its Challenge

Cambodia intends to have all the recognized minefields cleared by the end of 2030. At that time, all that will be left to clear will be the hundreds of thousands, possibly millions, of pieces of unexploded ordnance (UXO) that litter the country. The world is still clearing UXO from WWI, which ended in 1918. The problem here will go on for years.

Those who experienced and grew up during the fighting, which only ended in the late 1990s, still suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome (PTSD). Cambodia never declared war on anyone, yet they were the victims of nearly 35 years of warfare, overflowing from the American involvement in Vietnam. It will not recover without help.

The Cambodia Landmine Museum stands as a stark reminder of what war, and landmines in particular, did to a tiny child. Multiply that by millions, and you see Cambodia's situation for the past 60+ years. The museum is modest. One man built it to tell his story and encourage visitors to bring that home and end the use of landmines worldwide. It was built and funded by donations and ticket sales, without millions of dollars from governments and foundations. Yet its simplicity resonates with visitors from around the world.

The Cambodian government licenses the museum and works harmoniously with the country's demining authorities. Aki Ra has been honored by organizations worldwide for his work. In 2010, he was one of CNN’s Top Ten Heroes. More than 10,000 nominations were made for ‘people making a difference,’ and Aki Ra was one of 10 chosen to be honored. 2012 Aki Ra won the Manhae Grand Prize for Peace in South Korea.

I (the author Bill, who is of European descent) was once asked if I was Cambodian, I said I was, and that I am American, German, Chinese, Australian, and Russian. I said I am a child of this planet. I asked the student if she agreed. She did. So I told her she was my sister and I was her brother. And when your brother falls down, you give him your hand. That is what the Cambodian Landmine Museum does.

[1] Inspired by the teachings of Mao Zedong, the Khmer Rouge came to espouse a radical agrarian ideology based on strict one-party rule, rejection of urban and Western ideas, and abolition of private property. “Origins of the Khmer Rouge” from United States Holocaust Memorial Museum