THE SEVENTH ISSUE OF FIHRM-AP - From Bedroom to Gallery: Exploring Queer Identity in 1980s Australia

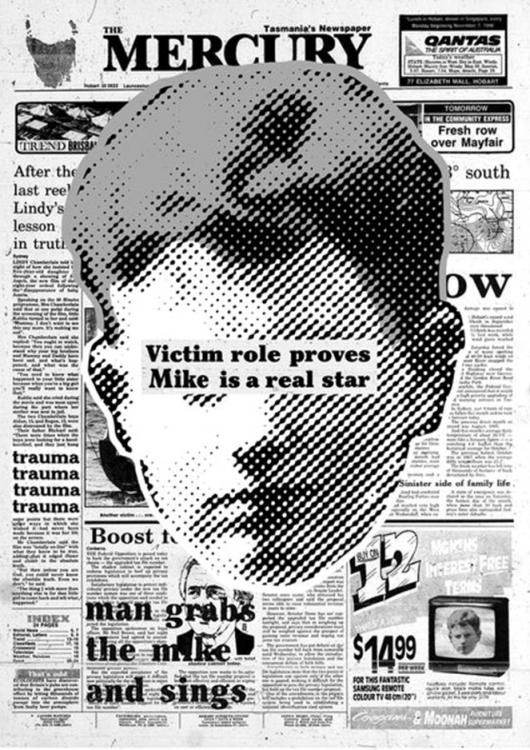

MIKE! My Pop Life, 2022 (installation view). Plimsoll Gallery, Tasmania.

About MIKE!

Michael Brady (aka MIKE!) is a multi-disciplinary queer artist and designer based in lutriwita/Tasmania whose work includes drawing, printmaking, photography and digital media. Brady's focus is sharing LGBTIQIA+ stories through artworks and immersive installations drawn from personal experience, history and popular culture.

About the Counihan Gallery

The Counihan Gallery is a free public gallery located in the heart of Brunswick, on Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Country. The Counihan Gallery opened in 1999 and is named in honour of the Australian artist and activist Noel Counihan (1913-1986), who was a champion of social justice and a vocal supporter of free speech. Their exhibition program reflects their commitment to political activism, sustainability, and creative expression.

From Bedroom to Gallery: Exploring Queer Identity in 1980s Australia

This article is written by Counihan Gallery curator Nicola Bryant, based on an interview with artist Michael Brady.

My Pop Life is an exhibition that will take place in 2024 at the Counihan Gallery. Can you tell us a little bit about the project?

My Pop Life is a semi-autobiographical art project that tells my coming-of-age story as a gay teenager in the late 1980s in the working class suburbs of nipaluna/Hobart, Tasmania. The exhibition comprises a series of collage-based posters presented in an immersive space that recreates my teenage bedroom, along with real and fabricated artefacts from the era. Each poster tells a version of the truth of my experience, drawing on history, memory and popular culture to present a personal account of my experience of being young and gay when it was still illegal in Tasmania and the subject of intense public debate. I use a methodology of ‘remixing’, in which artefacts and archival materials are examined and re-presented in new ways through a retrospective queer lens. These artefacts include pop posters, records, cassettes, collector cards, personal photographs, clothing, toys and teenage fan art. These are 'mixed' with new art and design elements to create a visual and written narrative that sometimes verges on fiction and fantasy.

For My Pop Life, you will recreate your bedroom from the 1980s. Why recreate the bedroom in 2024?

Recreating my teenage bedroom feels more necessary than ever. Five years ago, the Australian Marriage Equality Postal Survey reignited the same feelings of fear, shame and pride that I first experienced as a young queer person 30 years prior, which highlighted the need to further explore these themes in my work and revisit the My Pop Life project. By recreating my teenage bedroom in 2024, I hope to present an informative, entertaining and sometimes challenging time capsule of queer history, culture and personal experience while exploring issues and themes that affect the LGBTIQIA+ and broader community today. When recently undertaking historical research for this project, a surprising number of issues appeared in 1980s media that still attract attention and affect lives: LGBTIQIA+ rights are still debated in public and in parliament, global warming/climate change continues to wreak its human-made havoc on the planet, wars still rage, HIV/AIDS still affects millions of lives and injustice/discrimination rages on. Meanwhile, the media landscape has expanded in ways I couldn’t have imagined as a poor kid in Tasmania. Social media has shifted concepts of public and private irrevocably and queer representation has increased to the point of pink-washed mass commercialism. My project is informed by all of this, mixing the past and present to create an immersive experience that I hope is engaging, relatable and relevant. And everyone loves a bit of 1980s bedroom nostalgia, right?

This project has had iterations in the past. What changes occurred with each restaging of the project?

I first presented this project in 2007 in Hobart and in Melbourne as part of the 2008 Midsumma Festival visual arts program. It has since been exhibited numerous times in various spaces, changing and evolving with each iteration. The earlier exhibitions focused on popular culture, memory and teenage nostalgia story to tell my story in a universal way with subtle references to sexuality, history and politics. After a decade of resting the project, I decided to revisit the project in more detail as part of the Honours program at the University of Tasmania. The project now has a greater focus on LGBTIQIA+ issues and events happening outside my bedroom in Tasmania at the end of the 1980s, based on historical research and a deeper exploration of my own history. As a result, the project has become more political in content and theme. Visually, the project has evolved to include many more poster-based works that use text to engage directly with the viewer, using new and existing materials drawn from popular culture, mainstream media and contemporary art. The bedroom installation also includes an increasing number of objects, as I continue to archive my collection of original and sourced artefacts.

Posters are linked to mass production and advertising, but also to protest, and art and design. While we often think of posters as facing outward to the public, on streets or on placards, they also have a life inside the bedrooms of young people. Why do you think this is and why was it important to you?

The bedroom poster has always been the primary visual component of my project; it relates to the common teenage ritual of decorating a private space that reflects personal interests and identity. In reflecting on my own teenage experience, I saw this process as a necessary way of creating a safe space where a carefully considered display of posters of pop stars - many of whom were queer icons - mirrored an increasing awareness of my own sexuality. Pop posters aren’t generally considered political in nature, but they did communicate something that was bigger than my own experience, often using visual codes that referenced LGBTQI+ issues in a global cultural and political context. Many queer pop stars, photographers, stylists and designers used the poster as a means for communicating messages relating to HIV/AIDS, such as queer singer Jimmy Somerville wearing an ACT UP t-shirt in an otherwise innocuous pop poster. Like music videos and advertising, sexuality was expressed via the poster in a way that a pubescent teenager like myself could not resist. In their own commercially-driven way, many of the pop posters I blu-tacked onto my bedroom walls promoted ideas of inclusiveness, self-expression and pride in cool and colourful ways that were in complete contrast to mainstream media representations of LGBTIQIA+ issues at the time. I also reference political posters, advertising and art to create works that mix political slogans with pop culture imagery and personal stories: tapping into the power of the poster as a medium for mass communication. Much of my inspiration comes from Queer Tasmanian-born artist, designer and activist David McDiarmid (1952-1995), who designed and illustrated posters for the LGBTQIA+ community through the 1980s and early 1990s and made artworks that used newspaper articles, pop culture imagery, pornography and artefacts as materials to create collage-based and digitally created works that communicated something bigger than the sum of their borrowed, stolen or copied parts. McDiarmid’s 32 page zine Toxic Queen and series of text-based posters Rainbow Aphorisms in particular, have been a key influence on my project. Both series harness the power of language and queer humour to communicate McDiarmid’s personal experience of HIV/AIDS and to challenge negative media representations of queer life and people.

The HIV/Aids epidemic in the 1980s brought LGBTQI+ issues into mainstream media, where previously it was not acknowledged. The project seems to have a tension between what is public, and what is private. Is this something you think about in your work?

Absolutely. There is a deliberate tension in my work which reflects the mood of the era, particularly in relation to the LGBTIQIA+ experience. I was still quite young when the HIV/AIDs hit mainstream media, much of which I watched unfold on TV. The death of American actor Rock Hudson in 1985 was my first exposure to HIV/AIDS, which by then was a world wide epidemic. Closer to home, the 1987 Australian Government funded ‘Grim Reaper’ advertising campaign to raise awareness about HIV/AIDS was a significant cultural, social and political moment that I remember vividly and which successfully instilled in me both a fear of HIV/AIDS and my burgeoning queer identity. Much of this fear was in response to private lives being openly debated in public forums, which inevitably generated further tension, divisions and conflicting messages around what it meant to be young and queer.

MIKE! My Pop Life, 2022 (installation view). Plimsoll Gallery, Tasmania.

What is the importance of bringing a personal space, like a bedroom, into a public space like the Counihan Gallery?

I think its’s important for artists to share personal and private experiences in public spaces, particularly for marginalised communities whose lived experience is not necessarily reflected in mainstream media or advertising. While much has changed and improved regarding the rights and representation of queer people in recent decades, I feel there is still the need to tell our stories and share our experiences to a broader audience. By inviting the audience into my teenage bedroom, I hope to create a safe queer space for telling my story and for visitors to reflect on their own experience, queer or otherwise. I think that public galleries have become increasingly safe spaces for queer artist to present their work; the Counihan Gallery has an impressive history of presenting personally and politically themed art and exhibitions, so it seemed the ideal space to present this project.

You describe the exhibition as using a ‘remix methodology’. Could you explain what you mean by this?

The remix for me is a physical and conceptual method of engaging with culture and ‘sampling’ existing materials to re-present them in new forms. For me it’s also a liberating mode of thinking/making that allows me to revisit the past and use selective memories and personal artefacts as materials for my project. In this way, my remix methodology affirms my agency as the subject of my story.

Artist and scholar Eduardo Navas describes remix culture as a global activity consisting of the creative exchange of information supported by the practice of cut/copy and paste in which pre-existing materials are ‘sampled’ and mixed into new forms, which neatly describes my practice. Culturally, the remix has origins in popular music, which is also referenced in my work. In either case, the outcome is a reworked original; reimagined and reinterpreted to appear both fresh and familiar. Navas specifically describes the ‘selective remix’, where the artist adds to and deletes parts from the original source material while leaving its 'spectacular aura' intact. This idea of the ‘spectacular aura’ is really interesting to me and immediately reminds me of David McDiarmid’s work, which I consider to have a particular style and substance that is both spectacular and intrinsically queer.

You talk about celebrating queer culture, but it seems as though there is also a lot of pain bound up in this project. Why do you think it was important to include celebration as part of this exhibition?

I think that there is a need for celebration, affirmation and acceptance in the LGBTIQIA+ community, which has been demonstrated through decades of protest, parties, popular culture and art. The concept of ‘pride’ has emerged to define this need, which I have a somewhat complicated relationship with. I am still on a journey of self-acceptance and ‘pride’ in my identity as a queer person and artist; largely the result of the discrimination and negative representations that myself and other LGBTIQIA+ people have been subjected to for decades. On a more personal note, my experience as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse is a difficult but necessary subject I also explore in this project. Pain and trauma are defining aspects of my story, but they are juxtaposed with the celebratory nature of queer and popular culture to convey joy as well as pain. As a young person, I immersed myself in the colourful world of popular culture to escape the reality around me; for this project I also use it as an accessible way explore difficult topics. Ultimately, My Pop Life is a coming of age story and a celebration of life in the face of adversity, which is something I think most people can relate to.